"Buy discount emorivir 200mg, hiv infection rates sub saharan africa".

By: G. Tangach, M.B.A., M.D.

Professor, Southwestern Pennsylvania (school name TBD)

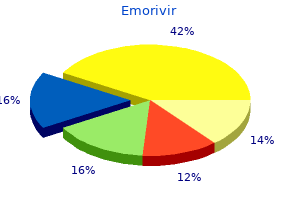

Unlike the rest of archaic Homo sapiens hiv infection rates in europe discount emorivir 200 mg, Neanderthals are easily defined and identified in many ways hiv infection rates massachusetts buy cheap emorivir 200mg line. There is a clear geographic boundary of where Neanderthals lived: western Europe, the Middle East, and western Asia. The time period for when Neanderthals lived is widely accepted as between 150,000 and 35,000 years ago. Additionally, Neanderthals have a unique and distinct cluster of physical characteristics. While a few aspects of Neanderthals are less clear cut and are shared among some archaic Homo sapiens, such as the types of tools they created and used, most attributes of Neanderthals, both anatomically and behaviorally, are unique to them. As mentioned previously, the geographic distribution of Neanderthals is very specific. Neanderthal fossils, thus far, have been found across a narrow latitude of western Europe, the Middle East, and western Asia. No Neanderthal fossils have ever been discovered outside of this area, including Africa. While Neanderthals lived in different ecosystems, including temperate environments, they were very well adapted to extreme cold weather and their geographic distribution includes what would have been some of the coldest habitable locations at the time of their existence. Neanderthals lived during some of the coldest times during the last Ice Age and at far northern latitudes. This means Neanderthals were living very close to the glacial edge, and not in a more temperate region of the globe, like some of their archaic Homo sapiens relatives. Their range likely expanded and contracted along with European glacial events, moving into the Middle East during glacial events when Europe became even cooler, and when the animals they hunted would have moved for the same reason. During interglacials, when Europe warmed a bit, Neanderthals and their prey would have been able to move back into Western Europe. Brain size is one of the Neanderthal features that continues to follow the same patterns as seen with other archaic Homo sapiens, namely an enlargement of the cranial capacity. The average Neanderthal brain size is around 1,500 cc, and the range for Neanderthal brains can extend to upwards of 1,700 cc. The majority of the increase in the brain occurs in the occipital region, or the back part of the brain, resulting in a skull that has a large cranial capacity with a distinctly long and low shape that is slightly wider than previous forms at far back of the skull. Modern humans have a brain size comparable to that of Neanderthals; however, our brain expansion occurred in the frontal region of the brain, not the back, as in Neanderthal brains. This difference is also the main reason why Neanderthals lack the vertical forehead that modern humans possess. They simply did not Archaic Homo 411 need an enlarged forehead, because their brain expansion occurred in the rear of their brain. Due to cranial expansion, the back of the Neanderthal skull is less angular (as compared to Homo erectus) and is more rounded, a feature similar to that of modern Homo sapiens. Another feature that continues the trend noted in previous hominins is the enlargement of the nasal region, or the nose. Neanderthal noses are large and have a wide nasal aperture, which is the opening for the nose. While the nose is only made up of two bones, the nasals, the true size of the nose can be determined by looking at other facial features, including the nasal aperture, and the angle of the nasal and maxillary, or facial bones. In Neanderthals, these indicate a large, forward-projecting nose that appears to be pulled forward away from the rest of the face. This feature is further emphasized by the backward-sloping nature of the cheekbones, or the zygomatic arches. The unique shape and size of the Neanderthal nose is often characterized by the term midfacial prognathism-a jutting out of the middle portion of the face, or nose. This is in sharp contrast to the prognathism exhibited by other hominins, who exhibited prognathism, or the jutting out, of their jaws. The teeth of the Neanderthals follow a similar pattern seen in the archaic Homo sapiens, which is an overall reduction in size, especially as compared to the extremely large teeth seen in the genus Australopithecus.

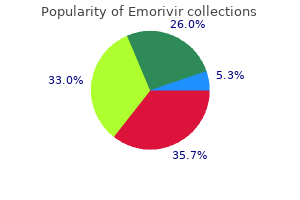

The gracile frame and neurological anatomy allowed modern humans to survive and even flourish in the vastly different environments they encountered infection rates of hiv cheap emorivir 200 mg online. Based on multiple types of evidence antiviral substance order emorivir 200 mg amex, the source of all of these modern humans, including all of us today, was Africa. This section traces the origin of modern Homo sapiens and the massive expansion of our species across all of the continents except Antarctica by 12,000 years ago. While modern Homo sapiens first shared geography with archaic humans, modern humans eventually spread into lands where no human had gone before. Starting with the first-known modern Homo sapiens, around 315,000 years ago, we will follow our species from a time called the Middle Pleistocene to the end of the Late Pleistocene. Culturally, we will trace developments from the Middle Stone Age through the transition around 50,000 years ago to the Later Stone Age, when cultural complexity quickly grew with both technology and artistry. We will end this section right before the next big cultural change, called the Neolithic Revolution. A few notes on this part of the chapter: It is organized from past to present when possible, though a lot happens simultaneously to our species in that time. I encourage you to make your own timeline with the dates in this part to see the overall trends. Search for these scientific papers online to see how researchers reach the conclusions presented here. Note the growth in area starting in Africa and the oftentimes coastal routes that populations followed. The earliest dated fossils considered to be modern actually have a mosaic of archaic and modern traits, showing the complex changes from one type to the other. Experts have various names for these transitional fossils, such as Early Modern Homo sapiens or Early Anatomically Modern Humans. However they are labeled, the presence of some modern traits means that they illustrate the origin of the modern type. Three particularly informative sites with fossils of the earliest modern Homo sapiens are Jebel Irhoud, Omo, and Herto. Recall from the start of the chapter that the most recent finds at Jebel Irhoud are now the oldest dated fossils that exhibit the traits of modern Homo sapiens. In total there are at least five individuals, representing life stages from childhood to adulthood. For example, the skull named Irhoud 1 has a primitive brow ridge, while Irhoud 2 and Irhoud 10 do not (Figure 12. The braincases are lower than what is seen in the modern humans of today but higher than in archaic Homo sapiens. The teeth also have a mix of archaic and modern traits that defy clear categorization into either group. Research separated by nearly four decades uncovered fossils and artifacts from the Kibish Formation in the Lower Omo Valley in Ethiopia. These Omo Kibish hominins were represented by braincases and fragmented postcranial bones of three individuals found kilometers apart, dating back to 195,000 years ago (Day 1969; McDougall, Brown, and Fleagle 2005). In more recent fieldwork, an informative section of the Omo I pelvis was found in a re-excavation in 2001. Hammond and colleagues (2017) found that the measurements and observations were in line with modern Homo sapiens, although larger in absolute size and robusticity. Also in Ethiopia, a team led by Tim White (2003) excavated numerous fossils at Herto. There were fossilized crania of two adults and a child, along with fragments of more individuals. The skeletal traits and stone tool assemblage were both intermediate between the archaic and modern types. Features reminiscent of modern humans included a tall braincase and thinner zygomatic (cheek) bones than those of archaic humans (Figure 12. The cranium included an angled occipital bone and was longer than in present-day modern Homo sapiens.

Buy discount emorivir 200 mg online. HIV - AIDS - signs symptoms transmission causes pathology.

Mignonette Tree (Henna). Emorivir.

- What is Henna?

- Are there safety concerns?

- Are there any interactions with medications?

- Ulcers in the stomach or intestines, dandruff, skin conditions, severe diarrhea caused by amoebas (amoebic dysentery), cancer, enlarged spleen, headache, yellow skin (jaundice), and other conditions.

- How does Henna work?

- Dosing considerations for Henna.

Source: http://www.rxlist.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=96827

Of course antiviral drugs pdf emorivir 200mg low price, such increases may not continue forever as they are energetically expensive when do primary hiv infection symptoms appear purchase emorivir 200 mg with visa. As with all acclimatory adjustments, an increase in the basal metabolic rate is merely temporary. Another form of a temporary heat-generating acclimatory adjustment to cold stress is the physiological response of shivering. Shivering results when the hypothalamus stimulates increased muscular activity that leads to an elevation of the muscular metabolism. Much like the increased muscular metabolism that occurs during periods of strenuous exercise, the elevation of muscular metabolism rates during shivering leads to higher rates of body heat generation. Human Variation: An Adaptive Significance Approach 521 Other physiological mechanisms the body uses to assist with the maintenance of temperature related to homeostasis involve the preservation of heat already contained within the body. Of these mechanisms, the most notable is the constriction of peripheral capillaries in the skin through a process called vasoconstriction. The decreased surface area of the capillaries through vasoconstriction results in less heat reaching the surface of the skin where it would be dissipated into the atmosphere. In addition, vasoconstriction leads to the maintenance of heat near the core of the body where the vital organs are located. This is one of the reasons that an individual may experience cold-related injuries, such as frost-bite leading to tissue necrosis (tissue death) in regions of the body that are most distant from the core. Just as cold stress presents challenges to maintaining homeostasis within the body with respect to temperature, heat does as well. In hot climates, the body will begin to absorb extra heat from its surroundings (through conduction, convection, and radiation) resulting in potential heat-related disorders, such as heat exhaustion. All humans, regardless of their environment, have approximately the same number of sweat glands within their bodies. Over time, individuals living in hot, arid environments will develop more sensitive forms of sweat glands resulting in the production of greater quantities of sweat. In an effort to prevent dehydration due to this form of acclimatory adjustment, there will be an additional reduction in the volume of urine produced by the individual. As noted in the previous section, some cultural groups, particularly those in equatorial regions, add pungent spices to their foods to inhibit the colonization of bacteria (Sherman and Billing 1999). Although the addition of spices to foods to decrease spoilage rates is a behavioral adjustment, the application of some forms of peppers triggers an acclimatory adjustment process as well. Capsaicinoids are produced by the plants to deter their consumption by some forms of fungi and mammals. When mammals, such as humans, consume the capsaicinoids from chili peppers, a burning sensation may occur within their mouths and along their digestive tracts. Although the peppers themselves may be at ambient temperature so their consumption is technically not causing any form of body temperature increase, the human body perceives the pepper as elevating its core temperature due to the activation of the capsaicin receptors. In addition to increased sweat production in the body as a means of regulating internal body temperature to maintain homeostasis, vasodilation may occur (Figure 14. Vasodilation occurs when there is an expansion of the capillaries within the skin leading to a more effective transfer of heat from within the body to the exterior to allow conductive, convective, radiative, and evaporative (sweating) processes to occur. Physiologically-based acclimatory adjustments to hot, dry climates may be complemented by behavioral adjustments as well. For example, individuals in such climates may limit their physical activity during the times of day when the temperature is typically the hottest. Additionally, these individuals may wear loose fitting clothing that covers much of their skin. The looseness of the clothing allows for air to flow between the clothing and the skin to permit the effective evaporation of sweat. Acclimatory Adjustments: Altitudinal Stressors the challenges posed by thermal conditions are but one form of environmental stressor humans must face.

From the point of view of aviation hiv infection period generic 200mg emorivir otc, it is important to note that these illusionary effects occur even in a well- illuminated cockpit if external visual reference is absent or ill-defined hiv infection rate south korea emorivir 200mg lowest price. There is a curious difference in the aftereffects of active and passive whole-body rotation. The reader can demonstrate this to himself by standing and, with arms folded, executing eight, smooth, continuous ambulatory turns in about 20 seconds with eyes closed. Upon stopping (eyes still closed), if the body is allowed to remain fairly relaxed, the head, torso, and legs tend to twist in the same direction as the previous turn. The motor effects are in the expected compensatory direction from the deceleratory stimulus to the semicircular canals; they are compensating for a body motion which is not taking place. Under this circumstance, the aftersensation in most individuals is not one of turning in opposite direction, as would be predicted from the semicircular canal response, but rather of turning in the same direction as the preceding turning motion. First, it illustrates that unusual vestibular stimuli can induce reflexive motions of the head, torso, and limbs that may not be appreciated by the pilot, yet they may influence performance. Secondly, the difference in aftersensation between active and passive turning may have implications for the perceptual experiences of pilots who actively generate unusual vestibular stimuli in flight maneuvers and, of course, continue to control the aircraft after maneuvers are completed. Experienced pilots develop what is referred to as "fusion," in which the aircraft is said to become a mere extension of their voluntary control of motion (Reinhardt, Tucker & Haynes, 1968). Thus, the sensations of experienced pilots are probably shaped by their active control functions and may 3-28 Vestibular Function be a little different than would be deduced from passive stimulation in laboratory devices. This would account for several indications that experienced pilots are much more disturbed by fixedbase flight simulators (Reason & Brand, 1975) with moving visual scenes than is the novice. Somotogravic and Oculogravic Illusions the somotogravic and oculogravic illusions are sometimes referred to as the otolithic counterparts of the somatogyral and oculogyral illusions. They are apt to occur when the head and body are in a force field which is not in alignment with gravity, a condition that occurs frequently during flight and which is usually studied in the laboratory by means of a centrifuge. Although otolith stimulation plays a role in the effects of such stimuli, certainly other somatosensory receptors are also involved. Individuals without vestibular function experience these "illusions," although their perceptions differ somewhat from those of individuals with vestibular function (Graybiel & Clark, 1965). The perception of feeling upright during a coordinated bank and turn (Figure 3-7) or its converse of feeling tilted when the resultant force field is not aligned with gravity, has been referred to as the "somotogravic illusion" (Benson & Burchard, 1973). For situations in which an observer views a line of light and either estimates its apparent tilt or attempts to adjust it to apparent vertical, the perceptual error has been called the "oculogravic illusion" (Graybiel, 1952). However, the important point for the aviator is that accelerations in flight can yield a resultant force vector which may be perceived as upright, even though it is substantially "tilted" relative to gravity. Even in a diving turn, the resultant force can give the illusion of approximately level flight. Concentrating on maintaining positive relative to another aircraft, the pilot may feel approximately straight and level while in rapid descent. Even on a clear day over water, the horizon may not be immediately locatable, without immediate clear visual reference. While the direction of the resultant force vector provides a fairly close approximation of the subjective vertical in "steady state" conditions. One such departure results from conditions of dynamic (changing over time) linear and angular accelerations, as explained in the previous discussion of the coding of vestibular messages. The otolith stimulation is as though the head and body had rotated backward relative to gravity, but, because the head is fixed in an upright position, there is no angular acceleration to stimulate the vertical semicircular canals. Under these circumstances, the immediate perceived change in orientation is usually less than that which would be calculated from the immediate stimulus to the otolith (Guedry, 1974, p. This kind of situation occurs in linearly accelerating or decelerating aircraft, and, though some change in attitude is experienced, if the head does not rotate on the neck during the linear acceleration or deceleration, then the experienced change in attitude is probably less than the dynamic rotation of the linear acceleration resultant vector and hence closer to the actual attitude of the aircraft. Even so, there can be enough change in perceived attitude to introduce dangerous reactions in flight (Collar, 1946). An extreme example of this kind of stimulus occurs during a catapult launch from an aircraft carrier (Figure 3-10) (cf. When resolved with gravity, the resultant linear acceleration vector makes an angle of about 77 degrees relative to gravity.